2006 09

David Miles and Melanie Baker discuss the differences between the US and UK housing markets, suggesting that only so much can be inferred from the UK experience for the US. While there are structural differences between the UK, Australian and NZ housing markets and their financing, I don’t think these differences make a compelling argument that the cyclical implications of housing weakness in the US will differ substantially from the generally benign experience of the rest of the Anglo-American world. Indeed, Miles and Baker share my view that the nexus between housing and consumption that Dr Strangelove (aka Nouriel Roubini) relies on for his US recession call is not as strong as conventionally assumed:

one should be sceptical on the strength of the link between housing markets and consumer spending. Although we agree that there is a degree of linkage (e.g., through changes in housing market activity driving purchases of certain types of household goods and through changes in the available collateral for household borrowing — home equity withdrawal is more than 5% of disposable income in both the US and the UK), this linkage is probably variable over time and may not even be especially strong.

Three points are significant: 1) just because house price movements and consumer spending movements may be correlated, this does not imply a causal relationship between them. An observed correlation may simply reflect movement in other factors which affect both house prices and consumer spending, e.g., interest rates, labour market fundamentals and income expectations; 2) Just because housing constitutes the largest part of household wealth (at around 54% in the UK once pension and life insurance assets are included), it does not follow that the value of housing has a very strong influence on consumer spending. Housing is not like other types of wealth. Most people live in the house that they own. If an owner is preparing to trade up, i.e., move to a bigger house (as many throughout the housing market are), then national house price rises do not make that household better off; 3). Those who trade down may gain from house price rises and those who trade up lose; these winners and losers should largely cancel each other out across the aggregate economy.

posted on 30 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The missing link in the recession scenario of Dr Strangelove and others is the transmission mechanism from weakness in US housing to the broader economy. There are two candidates in this regard: the direct contribution to growth from dwelling investment; and the impact of house prices on household net worth and consumption.

In relation to the first channel, the growth subtraction from dwelling investment is unlikely in itself to tip the US into recession, even allowing for some spillover into other demand components. Most doomsday scenarios rely more heavily on the second channel. Estimates of the elasticity of consumption with respect to house prices vary, but again do not suggest that a downturn in house prices is in itself sufficient to trigger recession. This is especially the case when we consider the potentially offsetting contribution to household net worth from gains in equity markets and the high levels of direct and indirect ownership of equities by the US household sector.

As my associates at Action Economics note, consumer confidence is proving resilient to the recent downturn in the housing sector:

Today’s consumer confidence data from the Conference Board round out a unanimous mix of confidence measures showing increases in September. We expect these gains to carry into October, given that the litany of positive influences on the indexes from energy prices, stock prices, bond yields, and news headline effects seem to be approaching the new month with encouraging trajectories.

Though today’s reported confidence bounce was hardly a surprise, it adds to the evidence that housing sector weakness is at least thus far still contained to this narrow sector. If the drop in real estate market prospects is to have a psychological impact on consumer spending, then presumably it should similarly impact confidence. As we noted in our commentary last week, it is unlikely that we will see a direct “wealth effect” of the housing market correction as long as rising stock prices leave a solid trajectory for household net worth overall.

It is often said that a downturn in house prices will lead people to ‘stop consuming.’ This is partly just sloppy language, yet few people seem to give much thought to how implausible this really is. The consumption share of GDP is typically fairly stable, not least because a large component of consumption expenditure is non-discretionary. While changes in consumption can certainly make a large contribution to (or subtraction from) growth in a given quarter, consumption is typically the demand component about which we should be least worried.

posted on 27 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Former federal Labor minister Barry Cohen, on lunch with Mark Latham:

Latham also has memory lapses. He forgot to mention what happened during lunch. Having raised three sons, we should have known better than leave my wife Rae’s prized piece of porcelain on the coffee table. Oliver, a two-year-old, picked it up and smashed it into a thousand pieces - at his father’s feet. It was not Oliver’s fault, but ours.

Rae showed remarkable restraint. White knuckles, an intake of oxygen and a gurgled “Oh, dear”, was her only indication of pain.

Mark showed even greater restraint. He didn’t even notice. No apology. No “I’m sorry”. No attempt to clean up the debris. Nothing. It was a minor incident in life’s rich tapestry but it revealed the true nature of Mark Latham.

As he departed, the First Lady hissed through gritted teeth: “If that bastard ever becomes leader of the Labor Party, I’m voting Liberal.” She kept her promise. Fortunately for Australia, she was not alone.

posted on 26 September 2006 by skirchner in Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Terry McCrann (sadly, no link, but see the dead tree edition of the Weekend Australian) responds to Ross Gittins’ latest martyrdom operation:

There is nobody in the media or economic policy and tax circles in any doubt that Costello looks at [George] Megalogenis in the same way he would at a rabid dog which had literally bit into his belly.

And that sits in this paper’ broader sustained, coherent and consistent critique of Howard government policy - especially on tax, but more broadly. If any single paper has got under Costello’s skin - but in a substantive not a snide sniping, Fairfax, way - it is The Australian. Just think Freedom of Information…

Someone like Gittins is “authorized” to write column after column of bilious personal opinion: essentially, I hate Howard. Occasionally if unintentionally interrupted by some substantive argument or fact.

And if Howard - in truth, someone in his office - were to respond, up goes the cry, a la this last column: bully-boy, attack on free speech, and really inanely pompous sentences like this one: “One isn’t supposed to write about such behind-the-scenes bullying, of course.”…

Gittins claims that Howard’s “big lie” was his scare campaign over interest rates. Yet in the very same column he argues that budget surpluses are critical to low rates; and attacks the government for not having bigger surpluses - causing rates to be a “fraction higher than otherwise.”

McCrann is just getting warmed up. Go get the print edition for more.

posted on 23 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Felix Salmon points to an article by Barry Eichengreen, which argues that:

Only the continued buoyancy of prices in Perth, in the far west of the country, has prevented prices nationwide from falling more dramatically. All this offers a hint of what the US has in store.

Unfortunately for Felix, this blog has already dealt with this argument:

The upswing in global commodity prices that began in 2002 explains much of this regional variation, adding to incomes in the resource-rich states and driving the inter-state migration flows that the RBA has identified as an important source of weakness in Sydney house prices, which have now largely converged back to the same ratio to other capital cities seen in the early 1990s. While many people have argued that, but for the commodities boom, the rest of Australia would look like Sydney, it is more plausible to argue that Sydney is only as weak as it is because the commodities boom has drawn people away from Australia’s largest city.

Eichengreen also wants us to believe that only the commodity price boom saved the Australian economy from a housing-led downturn:

So why is the Australian economy holding up so well? The answer comes in two parts. First, strong commodity prices are a boon for Australia. The country is a big producer of aluminium, copper, nickel, coal and iron ore, all of which are in strong demand globally, and especially in neighbouring [sic] China. To Australians it seems as if there is no end to China’s demand for these commodities.

While the boom in commodity prices has certainly been important to the Australian economy, it hasn’t done as much for measured GDP growth as many analysts would like to think. Most people would be surprised to learn that mining output in Australia fell 8.3% in the year to June. Net exports have made a flat or negative contribution to Australian GDP growth in every quarter since Q3 2001 (a fact that should not have escaped an ersatz doomsday cultist like Felix!) As John Edwards likes to point out, Australian export volumes have even underperformed US export volumes. The increased national purchasing power due to a rising terms of trade has resulted in the substitution of imports for domestic production, which subtract from GDP. Where the commodity boom shows up is in growth in gross domestic income, which has held up significantly better than GDP growth. However, given the high level of foreign ownership of the Australian resources sector, this partly benefits foreign equity owners (see Australia’s net income deficit, much maligned by Nouriel). If Australia were anywhere near as reliant on commodities as many analysts seem to believe, then the Australian economy really would be in dire straits.

While many pundits are desperate to believe that the US is destined for housing-led economic ruin, there is little support for this proposition in the experience of the other Anglo-American economies that have been front-running the US housing cycle.

posted on 20 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

News Ltd maintains its scrutiny of the Reserve Bank by way of FoI legislation:

GREAT to see the due process that goes into appointing the people who set our interest rates. While Glenn Stevens took over this week from Ian Macfarlane as governor of the Reserve Bank, an appointment properly trumpeted several weeks ago, there was no such announcement about the future of board member Warwick McKibbin, whose five-year term was to end on July 30. As business closed on Friday, July 28, there was still no official announcement about his future, which was a bit of a concern as board members are usually sent the board papers by secure courier the Friday* before a Tuesday meeting. So, with no official announcement, did the bank send McKibbin the papers for the meeting on August 1? A Freedom of Information request to the bank has revealed that they did, but only after a third “oral reassurance” from Treasury that McKibbin was staying in his job. RBA secretary David Emmanuel was told by Treasury on July 19 that the re-appointment had been cleared but Treasurer Peter Costello had yet to sign the letter. By Thursday, July 27, Treasury told the bank the Treasurer had signed off and the announcement would be made on Friday. It wasn’t, but Treasury still advised that it was all legal and would go ahead. McKibbin got his papers, the board met and increased interest rates. Phew.

* [actually Thursday, if memory serves - ed]

posted on 20 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Ross Gittins launches another one of his regular martyrdom operations:

except for people in privileged positions like mine, economists do have to be brave to stand up to the Howard Government with its behind-the-scenes bullying.

This is all a little bit precious, not least because it was a practice for which the former Labor Treasurer and Prime Minister, Paul Keating, was equally notorious, which is to say that none of this is anything new (and therefore hardly newsworthy). While there may be some economists at certain investment banks touting for government business who have to worry about such political pressure, that is a conflict of interest within the bank, not a problem with political pressure as such. If CEOs or their economists cave in to political pressure, it says more about them than it does about the government.

There was one occasion when I was working for Standard & Poor’s when I managed to get a phone call from the Prime Minister’s office, the Treasurer’s office and the office of the leader of the Opposition, all on the same day. Far from feeling any political pressure, I took considerable comfort from the fact that both sides of politics had been more or less equally annoyed. What was undoubtedly intended as political pressure was if anything useful feedback!

posted on 18 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(5) Comments | Permalink | Main

Since the Treasurer and incoming Governor of the Reserve Bank have largely recycled the previous Joint Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy to coincide with commencement of Glenn Stevens’ term as RBA Governor, it seems like a good occasion for me to recycle my previous criticisms of the governance arrangements for Australian monetary policy.

A curious feature of this and previous Joint Statements is the assertion that:

The Government and Bank continue to recognise that outcomes, and not the arrangements underpinning them, will ultimately measure the quality of the conduct of monetary policy.

At one level, this is an unexceptional statement: we do not want to privilege processes over outcomes. Yet by the same token, we are not indifferent to the way in which policy outcomes are achieved either. The fact that the government and RBA feel the need to say something about this betrays a certain defensiveness about the RBA’s governance arrangements, implicitly recognising that they are out of step with world’s best practice.

The RBA’s successful track record in the implementation of policy since the early 1990s effectively backs its claim that the ‘Nike’ or ‘just do it’ approach it shares with the Fed makes statutory reform of the RBA Act to put in place a more rigorous transparency and accountability regime unnecessary. There are also some supporting empirical studies, although isolating the effect of institutional arrangements on macro and financial market outcomes can be a fiendishly difficult exercise.

At the same time, the RBA has never gone so far as to say that a reformed governance framework would be detrimental to monetary policy outcomes (its actions with the government before the AAT in suppressing the release of information about the Board’s deliberations notwithstanding). What the government and RBA fail to recognise is that reform of the governance arrangements for the Bank may have procedural value that is independent of its implications for the actual conduct of monetary policy. Even if the actual policy outcomes were the same, the worst that could be said of a reformed governance framework is that these arrangements are superfluous. In fact, transparency and accountability are to be valued in their own right and not just for their implications for policy outcomes. Good policy outcomes are ultimately a poor justification for bad policy processes.

posted on 18 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

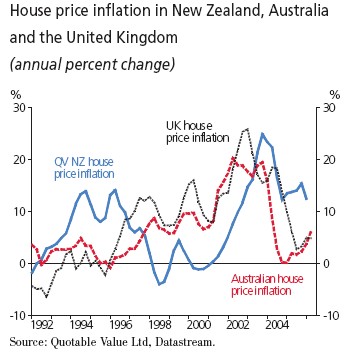

The forecasts of 20-30% declines in US house prices being offered by the usual suspects will be all too familiar to those in the rest of the Anglo-American world, which has been front-running the US housing cycle, and where such doom-mongering was also commonplace, at least until recently. Not so long ago, an article in the FT gave a run down of the long and disreputable history of doom-mongering in relation to UK housing. This week’s RBNZ Monetary Policy Statement produced the following chart, showing what has happened with UK, Australian and New Zealand house prices:

The experience of Australia and the UK is remarkably similar. The resilience of house prices in New Zealand reflects the sharp inversion of its yield curve, which has facilitated fixed rate lending below floating rates, so that the effective mortgage rate has not fully reflected the significant monetary tightening put in place by the RBNZ. Given the significant amount of NZ mortgage debt coming up for re-pricing over the next two years, the RBNZ is forecasting annual house price growth bottoming out at around -5% by the end of 2007, returning to flat growth by the end of 2008, but the RBNZ admits that housing has proven much more resilient than it expected.

posted on 15 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

More of what Nouriel Roubini won’t tell you about the US economy, from my associates at Action Economics:

Today’s U.S. data on sales, prices, the labor market, and inventories all suggest that the widely assumed slowdown in the U.S. economy through the second half of the year is proving more modest than some fear, with none of the periodic and clumsy downside adjustments that have thus far been contained entirely to the housing market.

For retail sales, the report revealed slightly stronger than expected total sales through August, but a shift in the mix of sales to vehicles from other goods that reduce prospects for consumption growth in Q3—given that the auto data in the retail sales report are not “source variables” for the GDP calculation.

Retail sales overall continue to post healthy growth, with a return in y/y growth to the 6.7% area that is just below the lofty 7% figures generally seen through the prior twelve high-growth quarters of this expansion. The August y/y pop in growth followed a temporary dip in July to 4.5% that entirely reflected the hard comparison to last year’s July vehicle sales binge.

We now expect a hearty 3.5% real growth clip in consumption in the Q3 GDP report, following a 2.6% clip in Q2 that might be bumped down to 2.5%, and 4.8% rate in Q1. The implied downward adjustment to Q2 consumption in the final GDP report for the quarter was $1.5 bln.

Nominal consumption growth is poised to slow somewhat in Q3, in keeping with a modest slowdown in growth, despite the bounce in real growth. We project a stabilization of the savings rate around -0.7% in Q3 and Q4. The high 6.8%-7% nominal growth rates for consumption in Q1 and Q2 will be followed by a solid though lower 6% rate in Q3, and a projected 5%-6% rate in Q4 and beyond that is in line with the assumed economic slodown.

In total, the variations in consumer spending as gauged by this report through August are right in line with normal monthly and quarterly volatility, and are showing no sign that the economy is undergoing any sizable slowdown, as some fear. Though we continue to expect the downtrend in the savings rate through this expansion to transition to a sideways pattern through the second half of the year, and the monthly data are cooperating with this assumption, the transition is proving gradual.

posted on 15 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

ICAP economist Michael Thomas runs the speeches of leading central bankers through the Flesch-Kincaid test:

Australia’s central bank chiefs are easier to understand than their U.S. peers, though both lose out to straight-talking Bank of England Governor Mervyn King, according to a study by stockbroker ICAP Australia.

U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke’s speeches require listeners to hold a bachelors degree with honors, said Michael Thomas, ICAP Australia’s head of economics. By contrast, high-school leavers could understand the speeches of incoming Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Glenn Stevens, and ``on a good day, King could hold court at his local primary school,’’ Thomas said.

The study of recent speeches by central bankers used the Flesch-Kincaid test, which measures syllables per word and words per sentence, to assess how clearly a person speaks, and the education level a listener would need to understand the speaker. Former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan was famous for his sometimes obscure language—or, as Thomas put it, ``in his heyday, Greenspan could make a grocery list indecipherable.’’

Still, Greenspan outperformed Bernanke in the Flesch-Kincaid test, while both lagged Australia’s Stevens and the outgoing Reserve Bank Governor Ian Macfarlane.

posted on 14 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Another installment in our continuing series, dismissing the notion of house price inflation as a monetary policy-driven ‘bubble,’ this time from the Chicago Fed:

the housing boom has not been driven by unusually loose monetary policy. This is not to say that monetary policy has not been unusually loose, but that to the extent it has been loose, this is not what has been driving spending on housing. Second, the current levels of spending on housing are largely explained by the wealth created by dramatic technological progress over the previous decade. Third, changes in the demographic, income, educational, and regional structure of the population account for only one-half of the increase in homeownership. ... The last finding is that substitution away from rental housing made possible by technology-driven developments in the mortgage market, such as subprime lending, could account for a significant fraction of the increase in residential investment and homeownership. The current spending boom thus may be a temporary transition toward an era with higher homeownership rates and a share of spending on housing that is nearer historical norms.

(HT: Mark Thoma)

posted on 14 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

Andrew Norton now has his own blog.

posted on 13 September 2006 by skirchner in Misc

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

At least someone thinks Doomsday Cult Central is worth getting out of bed for:

I’ve taken a job at RGE Monitor, where I’m going to be setting up a new economics blog which I’m rather excited about. Launching soon – all ideas and suggestions gratefully received! (Not just on economics: any tips for how to get up every morning? I haven’t done it since December 2000, and I was woefully bad at it then…)

posted on 13 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Despite its name, Medibank Private is owned by the Australian government, which wants to sell it - though there seems to be some confusion within the Cabinet as to whether or not this year is the right time to do so.

One thing we can be sure of, though, is that public opinion won’t support it. In the 1980s, there was some popular support for privatisation, but it went into decline after major privatisations began in the early 1990s. Asked at an abstract level in 2005 (in the Australian Survey of Social Attitudes) whether privatisation brought more benefits than costs, 53% disagreed and 17.5% agreed. On more specific privatisations, some of the ‘don’t know’ respondents say ‘no’, with about two-thirds typically against the two main recent sale proposals, Telstra and Medibank Private. This was seen again in an ACNielsen poll published in this morning’s Fairfax broadsheets, with 63% against selling Medibank Private off and 17% in favour. Newspoll recorded almost the same result back in April.

Politically, I believe that marketisation and privatisation are contrary agendas - though in a policy sense they are synergistic agendas. The pragmatic Australian electorate wants reliable, cheap services, and as I argued last year in Telstra’s case if things are broadly ok people will stick with the safe status quo. Telstra’s service levels have improved significantly since the telecommunications market was opened up, and so removed the ‘do something, anything’ frustrations that were probably driving pro-privatisation opinion. Similarly, Medibank Private operates in a competitive market already so it is hard to see how privatisation will create any significant consumer benefits, and indeed as the Newspoll found most people think premiums would rise if it was privatised (though in reality competitive conditions in the industry will be the main determinant of prices).

The government isn’t likely to win this debate, but far more significant privatisations than Medibank Private have proceeded without obvious political cost, so they may as well take the cash from a sale if and when they can.

posted on 12 September 2006 by Andrew Norton in Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

We have previously noted the increased prominence that bowlderised versions of Austrian business cycle theory (ABCT) have assumed in popular discourse on macroeconomics and financial markets. Much of the appeal in ABCT rests in its seeming ability to provide a causal mechanism for what many people like to label as ‘bubbles’ in financial markets. Without this underlying causal mechanism, the notion of a ‘bubble’ is little more than a tautology invoked by people who can’t understand why economies and financial markets fail to adhere to their preconceived and often mistaken notions of appropriate behaviour

An article in the FT provides further evidence of the growing reliance on ABCT as a device to make sense of the economy and financial markets:

The investment theme of the autumn will instead be the vindication of the Austrian economists and their theories about the nature of the business cycle…

The aspect of Austrian economics that will be central to investment decision-making this autumn is the role of central banking in generating unsustainable investment booms and subsequent busts.

Yet there is little evidence to support ABCT as even a stylised account of business cycle and financial market dynamics, at least under current central bank operating procedures in the major industrialised countries, which have been dominated by interest rate and inflation targeting for at least the last 10 years.

The Taylor rule and related literature shows that it is much easier to explain monetary policy with reference to the economy than it is to explain the economy with reference to monetary policy. This is just another way of saying that monetary policy for the most part responds endogenously to economic developments and the exogenous component of monetary policy is very small. Anyone who has tried to motivate a role for official interest rates in standard economic models (the sort of empirical work that few Austrians are prepared to undertake) knows what a problematic exercise this can be.

This makes the claim that, but for the supposed monetary policy errors of central banks, the amplitude of business and asset price cycles would be greatly reduced extremely implausible, at least under contemporary interest rate/inflation targeting regimes. Indeed, we know that under the gold standard, the preferred monetary regime for many Austrians, volatility was more pronounced, with inflexibility in prices and exchange rates simply forcing any adjustment on to the real side of the economy.

The increased prominence of ABCT in popular discourse actually has profoundly anti-market implications, because it leads people to believe that there is something wrong with macroeconomic and financial market outcomes that are in fact largely market-determined and have very little to do with either monetary policy or ‘bubbles.’

posted on 06 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Australian higher education policy insists that all universities do research and that university education be as cheap as possible for students. Obviously, these two goals are in tension, with many costly aspects of the higher education system - such as teaching for less than half the year or libraries full of books of little use to undergraduates - designed entirely with research in mind. The policy structure has exacerbated this further by favouring research rather than student interests. For example, Commonwealth-supported student places are allocated to universities by a rigid quota system, with universities penalised for taking too many or too few students. This solves the bums on seats problem for most universities without them having to try very hard to do well by their students, since prospective students have few alternatives outside the state-sponsored system. By contrast, various incentive schemes encourage universities to increase the quantity and quality of their research output.

What this means in practice can be seen in amazingly frank comments from new Macquarie University Vice-Chancellor Steven Schwartz about what his university will do with the 25% increase in student charges that they intend to impose:

Macquarie vice-chancellor Steven Schwartz said about 20 per cent of the extra money would fund $1 million to $2million in new scholarships for needy students, especially those keen on science, maths or technology. ...

More fee income also would help Macquarie fund 40 new research positions advertised as part of a campaign to make the university more research intensive.

So it seems that the vast majority of Macquarie students will get exactly nothing in return for a major price hike. Since all Macquarie’s competitors have already done exactly the same thing and they are all protected by quotas Schwartz doesn’t even need to pretend that students could benefit from increasing their investment in higher education. Schwartz is actually one of the more pro-market VCs, and his own actions and comments show yet again why we need stronger market mechanisms in the higher education sector.

posted on 06 September 2006 by Andrew Norton in Higher Education

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

RBA Governor Macfarlane presides over his final RBA Board meeting today. Macfarlane has given more newspaper interviews in the last few weeks than in the last 10 year combined. In the latest interview, he complains about being verballed on the issue of tax cuts:

On the eve of his departure, Mr Macfarlane told The Australian Financial Review he saw little need to amass large budget surpluses just because the economy was growing solidly.

“I have heard people* say, `Oh, we should let the fiscal stabilisers work,’” Mr Macfarlane told the newspaper.

“I think they are working. I think if you have an economy that is growing at 3 per cent, as we have, there’s no reason why you would need bigger and bigger surpluses, in other words, why you would need to restrain it with some sort of fiscal restraint.

“What we have got is a tax system which is unintentionally much more income-elastic than anyone designed it to be or even thought it was, and so that even with the economy going at trend growth, we are pulling in a huge amount of taxes and pushing ourselves into surplus.”

Mr Macfarlane also endorsed Treasurer Peter Costello’s decision to deliver income tax cuts in his budget worth $36.7 billion over four years.

He said his comments on fiscal policy had been “shamefully misquoted” all year.

“I had no problem with what the Treasurer did in the May budget,” Mr Macfarlane said.

“The great irony - and I feel sorry for him in this respect - is that the same people who are urging him to make huge tax cuts have now turned around and said that what he did is pushing up interest rates.”

* [That would be you Ross Gittins! - ed]

posted on 05 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Andrew Norton will be guest posting temporarily at Institutional Economics. Andrew will already be known to most of you. He is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Independent Studies and an acting editor of its journal Policy. Andrew is a political theorist by training rather than an economist. This is something we actually have in common. I started out as a political scientist before re-training an economist, so we are both refugees from academic political science. His first post is below this one.

This is a good time to remind people about procedures for commenting at Institutional Economics. Access to comments requires completion of a one-time registration and log-in process (click here to register). You must use a valid email address to register, but this need not be displayed in comments. If you access this site from more than one computer, you may need to log-in again to comment (if you are asked to enter an alpha-numeric character string with your comment, it means you are not logged on. Click ‘log-in’ in the black bar at the top right hand side of this page to log-in again. Andrew will be responsible for editorial decisions in relation to comments on his posts.

posted on 05 September 2006 by skirchner in Misc

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

At a meeting yesterday, the Australian Vice-Chancellors’ Committee agreed to change their structure and rebrand themselves as ‘Universities Australia’. This followed a highly critical review released last month.

From a public choice perspective, higher education interest groups have always been rather unusual. As I argued some years ago, they are among very few interest groups to campaign against their own financial interests by supporting restrictions on their fee-charging capacity. That’s a less common view today than when I wrote - somewhat reluctantly, they did agree to 25% increases in student charges back in 2003 - but it is still widely held. This is only partly conventional egalitarian concerns about student access. Rather, it is concern about inequality in Australian society as a whole, which they believe would be exacerbated by some universities becoming more ‘elite’ than they are today on the strength of high student fees. That’s why every public university is quite happy to enrol thousands of full-fee overseas students, but in many cases refuse to offer full-fee places to local students and suffer ideological angst when they do. The overseas students go home without changing Australia’s social structures.

Because these ideological hang-ups are still so prevalent, Universities Australia probably won’t be much more successful than the Australian Vice-Chancellors’ Committee. The central agencies wonder why they should spend taxpayer dollars on institutions that are so reluctant to take financial responsibility for themselves. Politicians wonder why they should spend money on institutions that rank lowly in the public’s spending priorities, and where the highest praise they are likely to get for spending initiatives is ‘a good start’. A new name, a new structure, and more effective lobbying methods are all part of what universities need in Canberra, but until they change their message they are never likely to remedy their serious financial problems.

posted on 05 September 2006 by Andrew Norton in Higher Education

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

|